financialreview.com – It’s Asia’s answer to Burning Man. And why not buy a villa, too? by Emma Rapaport

Meet the Russian tech multimillionaire who’s building a 44-hectare playground for adults in Bali.

What am I looking at?” I ask a long-haired man dressed in flowy white linen spruiking real estate opportunities at one of Bali’s hottest new music festivals.

“The future,” he replies, ushering me through the canvas curtains of a warmly lit tent.

No, this isn’t the metaverse or a page out of a Michael Crichton novel. It’s the promise of a new life at Nuanu, a 44-hectare, AI-managed “creative city” on Bali’s south coast.

I’m here for the city’s soft opening, which coincides with Suara – a three-day music, arts and wellbeing festival billed as Asia’s answer to Burning Man. As someone who thinks of themselves as a traveller rather than a tourist, I’ve long avoided Australia’s favourite international travel destination. So, I’ve accepted my commission to review Bali’s new beachfront hotspot with curiosity.

With its verdant landscapes, the so-called Island of the Gods is undeniably beautiful, but it’s earned a reputation for boozing Aussies and rapid overdevelopment. As a woman in front of me at the Jetstar bag drop explained, these days you have to “pick your spot” to come away with a heavenly experience.

Bali expats, be they digital nomads or cashed-up retirees, have meanwhile become frustrated with the woeful state of the island’s public infrastructure and the bumper-to-bumper traffic. Queue the development of Nuanu, the brainchild of Russian-born tech entrepreneur and multimillionaire Sergey Solonin.

Russian media is stacked with stories about the decline of Qiwi, the once $US3 billion payment services provider Solonin co-founded in the early 2000s. After posting record profits in 2022, when Russians found themselves cut off from cross-border transactions, Qiwi was delisted by Nasdaq in 2023 and then lost its bank’s licence in February. But the 50-year-old has put that life behind him, cultivating roots for himself, his wife and five children in Bali.

These days, coverage of the media-shy figure has a strikingly different feel. In a video floating around Facebook, Solonin says he only wants to do business with “people whom I want to hug”.

“In 2018 I said to myself that’s enough, I want to change again, and I went on a trip to search for new places and new ideas,” he tells me.

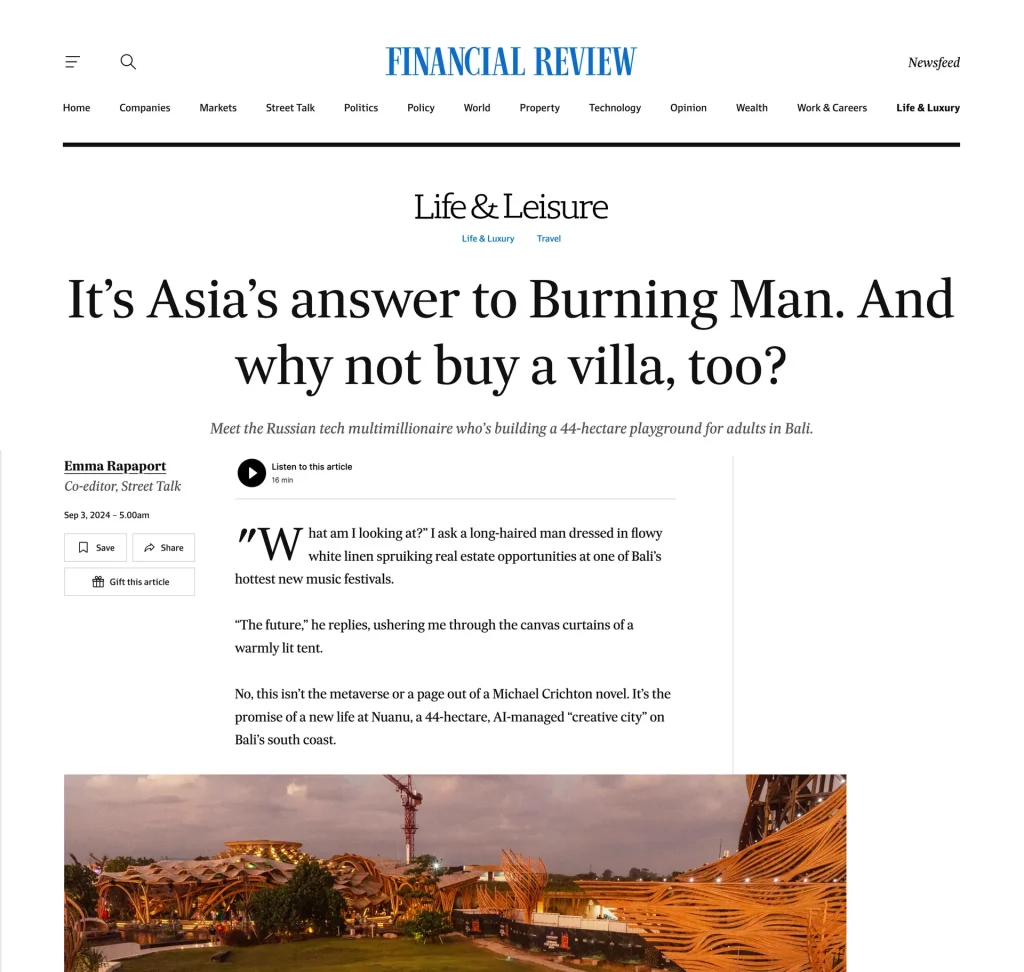

It’s difficult to describe what Nuanu is because heavy cranes still dominate much of the skyline, but I can tell you the dream: a community of creators, leaders and changemakers building a model of sustainable urban living. (Nuanu means ‘in the process’ in the local tongue.)

What is there now are the beginnings of a futuristic utopia with escapism at its core – a crisp white cave pool bar nestled into a cliffside; a multimedia jungle filled with interactive light installations that would put VIVID to shame; larger-than-life sculptures designed by world-renowned artists.

“In 2018 I said to myself that’s enough, I want to change again, and I went on a trip to search for new places and new ideas,” he tells me.

It’s difficult to describe what Nuanu is because heavy cranes still dominate much of the skyline, but I can tell you the dream: a community of creators, leaders and changemakers building a model of sustainable urban living. (Nuanu means ‘in the process’ in the local tongue.)

What is there now are the beginnings of a futuristic utopia with escapism at its core – a crisp white cave pool bar nestled into a cliffside; a multimedia jungle filled with interactive light installations that would put VIVID to shame; larger-than-life sculptures designed by world-renowned artists.

For its residents, Nuanu offers a 160-place international primary school and OXO The Residences, 40 luxury villas built to “to fill the gap for those looking for Western standards of living whilst in a vibrant tropical paradise”, according to the marketing spiel.

There are so many projects in the works it’s difficult to get them all on paper but it’s worth pointing out the mostly finished luxury boutique hotel Oshom, which is due to host executives from cryptocurrency giant Binance later this year. And how can I forget the alpaca farm, whose residents enjoy food flown in from the UK?

Solonin tells me more than $US100 million has already been spent on building Nuanu. Another $US400 million is expected to be sunk into the project by Solonin’s wealthy friends, venture capitalists and impact-investor types, many of whom attended the festival and toured around in a series of electric-powered buggies. These include investors from Europe, Indonesia, Australia, Singapore, Japan, Russia and even Ukraine.

Concrete jungle

Foreigners sinking millions into Bali developments is nothing new. Indonesia’s then-president Joko Widodo was so thrilled by investment in the island that he declared 10 more economic zones, turning serene fishing villages over to hotel chains eager to make a buck from the boom in tourism. But Bali’s drastic evolution has had its fair share of opposition from local communities seeking to protect their land and culture.

Nuanu’s cashed-up founder avers he’s building something different, taking a sustainable approach to development and working directly with the local community.

When I was told I wouldn’t, in fact, be staying in Nuanu because the hotel was still under construction, flashes of a Fyre Festival-style dream turned nightmare ran through my mind. But as we pull up to the compound on a stunning Saturday morning, superb twisting bamboo structures looming in the distance, it’s obvious no expense has been spared.

Turning off the crowded main street, past huge billboards promising 14.7 per cent returns on its villas and slogans like “It’s more than development, it’s art”, it is clear I am entering a new world.

I ask my driver what he makes of it all. He hasn’t been inside Nuanu as it has been closed to prying eyes during three years of development, but he points out just how much the landscape has changed in the past 10 years, from rice paddies stretching as far as the eye can see to western-style villas dotting the skyline and co-working spaces where the foreigners go “tap tap tap” on their computers.

I’m led up the path to a traditional Javanese-style house, where I’m meeting Solonin. I want to get a sense of what’s driving him to take on such an ambitious project, a world away from his former life. We sit on cushions on the floor around a small table, flanked by his brand and marketing manager and the head of brand and communications (whom I later find out is from a Balinese Brahmin family, the priest caste). Solonin’s bleached blonde hair is offset by a T-shirt so patterned and colourful, it’s hard to make out what I’m looking at.

An intentional life

As Solonin tells it, he took himself and his family on a round-the-world trip in 2018 in search of “a life that is different”. Several places spoke to him – Thailand, Kauai in the Hawaiian archipelago, and Bali, where they eventually settled in 2020.

“I was serious about Kauai… I was thinking about making a religion,” he says. “I was thinking I would find these different communities, bring them together, without dogma, and we will be together and trying to derive new values of the new world, working together and talking together.

“When I came to Bali, I looked at the cultural space, the story of Bali, and I thought here I want to do my community around arts and creativity.”

More than just a physical escape from the past, his goal is to live an intentional life.

“You live your life and after some time … it goes faster and faster, and that’s partly because you’re doing the same thing. You’re going from your work to your house, with your car, and you miss the whole trip, because you’re like a robot.

“If you change, then you start learning new things, discovering, all these processes slow down the perception of living, of time. That’s why I’m doing it, intentionally.”

But why, rather than enduring the headache of a multi-year development (with no end in sight), didn’t he just take his millions and buy a remote island, I ask.

“Imagine you had a few hundred million US dollars. You could buy a decent boat, an aeroplane, a big house. Imagine what you have there… You don’t have the best restaurant, you will never have the best spa. You can persuade someone to come cook for you but really great chefs will never come because it’s boring for them, even if you pay. At the same time, with the same money, you can build a city with the best restaurants, the best schools for your kids and for others. What would you choose?”

Naturally, making money is also a key driver, a fact that becomes clear when Solonin explains that they switched from building apartments to building expensive villas at Nuanu because “you want people who spend money”.

“It’s a big infrastructure [project] and so you want big cheques.”

The journey hasn’t been easy, however, as Bali’s complex property system throws up its own set of challenges. By law, foreigners cannot own property outright. Rather, they must team up with a local and take on a long-term lease. Before Nuanu, Solonin says, he tried to acquire 40 hectares in another part of Bali but “failed miserably” trying to negotiate with 14 families.

“Here [at Nuanu] there was a Balinese family who already owned a big chunk and we talked to them and I explained the project, a creative city. They returned two weeks later and said we want to do this because it’s something their father would have wanted.”

It’s worth noting this is far from Solonin’s first investment. He also has stakes in a raft of fintechs including the crypto mine BitFury, and education providers ****such as the Moscow School of Cinema. But this is his first property venture. He’s gone from IT guy to architect, he laughs.

Investors in Nuanu’s 32 projects include Bali-based developer Oxo Living and Russian vertical farming project iFarm, now headquartered in Finland. Nuanu provides the land and, in the case of Suara, the event space. The biggest success to date: selling $US30 million worth of property in four hours with partner OXO Residencies. These were snapped up by Indonesians, Singaporeans, Malaysians and, of course, Australians.

“Initially, I was just talking to some of my friends, asking them to collaborate,” Solonin says. “Someone wants to do a museum, someone wants to do a restaurant, and I just brought them together and said, ‘OK, I have this new city idea, let’s do it together.’ ”

We hug goodbye and I make my way back to the main stage of Suara, passing through waves of ultra-cool festival goers who look like the people who fill my TikTok “For You” page. By day, they lounge by the pool sipping Santai Seltzers and flit through the butterfly dome. By night, they grind to electric dance music and frolic through the magical light displays. It’s an influencers’ wet dream, each space more photo-worthy than the next.

While still in its infancy, the festival is an undeniable success, attracting more than 9000 people from over 60 countries. There’s something for everyone, with nine stages, 100 artists, yoga, talks, astrology readings, a KidsZone and markets offering flower crowns and “glam ups”. The DJ sets at the Luna Beach Club steal the thunder from the main stage at times, but everyone turns out for the headliner: Aussie music royalty Angus and Julia Stone.

#FollowYourVoice

Hunger draws me to the “global food court”, where I plop down at a table with two beautiful young French girls. Do I want a BO$$MAN burger or udon noodles with truffle-parmesan mousse and fresh Italian truffle slices? We get talking, and I learn they’re models flown in to up the event’s “cool factor” and spread the word to their social media followers.

It’s evident what vibe the organisers are going for. Suara, now in its third year, was co-founded by Jason Swamy, a founding member of Burning Man theme camp Robot Heart. His eyes shine with excitement as we sit chatting about his goals in the artist green room – a soon-to-be wedding chapel with the best ocean view in Nuanu.

“We want to become top five in the world. We want to set an example for the world of what contribution, community, culture and curation can be. We really put Asia and Bali on the stage on how to be responsible and what is amazing.”

There are elements that place the festival squarely in Bali – traditional dance workshops, canang offerings and an official opening ceremony presided over by the regional secretary of the Tabanan regency, in which Nuanu is located. But the European influence is plain as day, from the $650 beach-club day beds to the Berlin club-style rave scene under the night sky in the Labyrinth artist zone.

“I wanted to create a new festival brand, and Sergey said why don’t you just come in as a partner,” Swamy says. “So this year I officially took on the role of co-founder to internationalise the event.

It was previously more of a community event, he says, “focused on appeasing the powers that be – the government, the regional communities – because this a very sensitive place and you have to make sure you respect what Bali and Indonesia is about.”

For Nuanu – which, for all it has to offer, is a 30-minute drive from the nearest tourist hotspot of Canggu – the festival is a way to draw in people.

Surrounding us are accents from across the world – Dutch, Russian, British, Mexican, Cantonese… The two French girls, who have been in Bali for a few months, tell me everyone in the expat world seems to get along, lapping up their stint in paradise. But they note the tensions between the locals and the Russians who have flooded into Bali since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Unruly behaviour seems to be the crux of the problem, with influencers posing naked at cultural sites and driving with unofficial licence plates. Tensions hit a high last year when Bali governor Wayan Koster called for an end to Indonesia’s visas-on-arrival policy for Russian and Ukrainian citizens.

As an Australian, I feel hypocritical; my countrymen are well-known for flouting local customs and laws. But for the Balinese, it’s a new element, with a town down the road controversially dubbed ‘little Moscow’ on a local Instagram account.

This element is clearly on the mind of Nuanu’s developers. Back in the real estate tent, I ask the agent whether they’ve sold many properties to Russians. He tells me they’re trying to diversify the buyer pool.

A development in Ubud, Parq, has developed a reputation for being a Russian enclave, atop drawing anger from locals for clearing jungle and threatening the culture. Unlike Parq, which also describes itself as a city of the future, borscht is not on the menu at Nuanu.

Solonin acknowledges the problem of overdevelopment in Bali, but says Nuanu is about the opposite: preserving the nature and the culture of the area.

“If you look at what’s happening from Denpasar to Kuta, it’s all becoming too crowded. People come to Bali because of this nature, because of this culture, and that’s what we want to preserve here. We want to try and live differently, and see if that makes sense commercially.”

Nuanu tries to maintain a point of difference by displaying its sustainability credentials. These include a tree relocation program, a waste management facility, a social fund fed with revenue from its projects, and an art school that is free to local children. But that doesn’t stop a festival-goer, Geoff from New Zealand, jumping on the microphone at an open Q&A session to accuse the owners of destroying nature to make way for their development.

The comment evidently sets off alarm bells at Nuanu HQ because within hours I received a 360-word statement refuting his claims and insisting that “all buildings within Nuanu have been strategically placed in these open spaces to preserve as much of the original habitat as possible” and that “Nuanu has a policy to restrict construction to a maximum of 30 per cent of the land, preserving 70 per cent as green space.”

Geoff from New Zealand, a self-proclaimed environmental activist who claims to have exposed environmental damage around the world using drone footage, tells me his information about Nuanu comes from a Balinese woman who “knew about this area”. But when I asked if I can speak to her, things get a bit fuzzy.

As 5pm strikes, we make our way down to the festival entrance, where the Nuanu team is due to release 50 butterflies to give back to the ecology of the island. I can’t help but wince as they flutter through the drone that had been launched into the sky to document the event.

Would I be interested in buying a villa? Without a spare $1 million, I politely decline, but it’s hard to escape a conversation with a real estate agent without giving over your details, so now we’re connected on WhatsApp.

The writer was a guest of Nuanu.